From 18 November – 2 December, we’re celebrating the working-class heroines who brought grit and glamour to 1980s women’s cinema by screening Mai Zetterling’s brilliant Borstal ballad Scrubbers on The Cinema of Ideas. Alongside this, Susannah Buxton, who created the film’s costumes, will be in conversation with film historian and critic Pamela Hutchinson on Wednesday 24 November to discuss the making of and the impact of this astonishing film. Book now.

To accompany this event, Pamela writes about the historical context in which Scrubbers was made and the unforgettable women who were burning up the screen in this period.

Britain in the 1980s was officially a matriarchy, at the top level: the long regime of Thatcherism nested within the extended reign of Queen Elizabeth II. But far away from the palaces of Westminster and Windsor, women were holding the country together at home and at work, during a time of mass male unemployment and industrial decline. Britain’s working-class heroines may not have made many headlines, but they made their presence felt on the screen.

In his new book Films of Endearment, the US critic Michael Koresky has made the case for the 1980s Hollywood as home to a new flowering of the women’s picture. Inspired by his mother’s taste in cinema, he calls the decade “a lost paradise” filled with “multifaceted, headlining parts that weren’t merely doting wives or girlfriends” for “strong female stars, playing undaunted women blazing their own trails”. Something similar was happening in Britain, in a more transgressive, foul-mouthed, but always passionate way. These are the women I grew up watching, the heirs to Gracie Fields. Women with brave faces, loud voices and bright lipstick. Women who kicked against the pricks. Although it’s not often remarked upon, 1980s British cinema bursts with such unforgettable women, characterised by varying quantities of grit, glamour and girls-together solidarity: from the inmates of Mai Zetterling’s Scrubbers (1982) to the bathers of Joseph Losey’s Steaming (1985, adapted from Nell Dunn’s play). It was the era of Rita, Sue and not just Bob, too.

Hollywood’s Golden Age of the women’s picture came in the 1940s, a decade in which men were noted by their absence. With men at the front, women stepped into traditionally male workplaces and the established gender roles began to wobble – and so a film such as Mildred Pierce (1945) could explore what happens when women refuse to play housewife. In 1980s Britain, men were missing too, in a different way. There was a war in the Falklands, and continued military deployment in Northern Ireland, but rising unemployment meant many were out of work and at home on the dole. By the middle of the decade, the nation’s jobless were often on picket lines too. And so onscreen we saw women who might have expected to be housewives but were going out to work, struggling to feed their families and resisting the powers-that-be. And inevitably, women were broadening their horizons. The classic example is Julie Walters’ Liverpudlian hairdresser in Educating Rita (1983), who seeks a “better song to sing” through studying literature at the Open University, despite the discouragement of virtually everyone she knows, including her resentful spouse.

Rita is a dreamer. Like another Willy Russell creation, Pauline Collins’ Shirley Valentine, who tires of talking to her own kitchen wall and makes it all the way to Greece for a holiday romance with Tom Conti in the 1989 film. Or Welsh housewife Beryl, who finds escape and titillation at a stripshow with her best friends in Joanna Quinn’s riotous animated short Girls Night Out (1986). More romantically, Alexandra Pigg’s Elaine in Letter to Brezhnev (1985) follows her heart and petitions the Soviet Union for a chance of love and marriage with Ukrainian sailor Peter Firth. Even her best friend, Margi Clarke’s Teresa, Kirkby’s brave-faced glamazon, will finally admit she wants more out of life than “drinking vodka, getting fucked and stuffing chickens”. Some dreams are more poignant. In Alan Clarke’s TV drama Road from 1987, Lesley Sharp’s Valerie asks, at the end of her tether: “Can we not have before again?”

Because for the greatest working-class heroines in British cinema and especially TV, life in the 1980s was far from a fantasy, which is what galvanises them into action. Remember Walters, again, in Alan Bleasdale’s Boys from the Blackstuff (1982), berating her unemployed husband, played by Michael Angelis: “I’ve had enough of that ‘if you don’t laugh, you’ll cry’. Why don’t you cry? Why don’t you scream? Why don’t you fight back, you bastards? Fight back!” This outburst comes before she takes matters into her own bloody hands. Likewise, the women in Lynda La Plante’s Widows (1983-85) turn to crime after being left high and dry by their deceased robber husbands. And in Zetterling’s haunting, punk-styled Borstal drama Scrubbers even Kathleen (Elizabeth Edmonds), the mildest, best-behaved of the inmates, confesses she turned to shoplifting the minute her husband was made redundant: “When they threw my Terry on the slag heap at 21, I thought: ‘Right, you bastards, we’ll survive.’”

Kathleen isn’t the only inmate to clock that there’s more money to be made “pinching than working”, despite the risk. The Scrubbers rely on no one, not bosses or husbands, to rescue them from their cells, or situations that led them there. The film was first conceived as a sister to Alan Clarke’s violent prison drama Scum. However, when producer Don Boyd brought in a female director, the shape of the film began to change. Swedish Zetterling was the director of such forwardly feminist films as Flickorna (1968), a take on Lysistrata, which was screened as part of the ICO x Club des Femmes Revolt, She Said tour in 2018. Zetterling spent months doing “fieldwork”, as she called it, with her crew, meeting social workers and former prisoners and auditioning actors before casting “my loyal group of thirty unknowns”. Zetterling’s findings made their way directly to the screen in Scrubbers: first that the prison system was designed only to punish rather than rehabilitate, which only led to recidivism, and second that the inmates coped thanks to their “tough, earthy humour”. The jokes go toe-to-toe with the pathos in every scene and the Borstal girls fight, and riot and resist the system to the end. Why not when the warders bully them on work duty: “You’re not here to learn to be lady prime ministers, you know” and “Consider yourselves beaten and we’ll get on fine.” Zetterling concluded her account of the film in her memoir All Those Tomorrows, with a tribute to the resilience of the women who inspired it: “Without their black, ironic way of looking at the world, they would never have been able to stand it inside.”

One of those “unknowns” was a very young Kathy Burke, who plays the Borstal joker Glennis, a sweet-faced teenager with a potty mouth, addicted to cigarettes and solvents and bearing a tattoo that reads “Cut here” around her neck. When Burke recalled working on the film in a 2019 interview with The Guardian, she remembered the example that Zetterling set: “She was like a horse whisperer with me, really… she was constantly telling me: ‘You need to write, you need to direct, you need to create your own work.’ She wouldn’t stand for any crap, even in the 80s, when the industry was totally run by men.” Boyd’s account of the film backs that up, remembering how Zetterling stuck to her guns on everything from the violence to the profanity to the film’s sympathy for its protagonists, and ensured that Scrubbers expressed her own personal message: “Mai’s big thing was that people had this independent spirit that could shine despite the hellishness of a repressed system,” he told Robert Sellers in an interview for his book on Handmade Films, Very Naughty Boys. “She felt that very passionately about women, that women’s dignity should survive.”

Burke’s Glennis is a fantastic creation, a sign of future greatness to come from one of Britain’s very best working-class actresses, especially when she’s deep in a scatological monologue or talking her way into trouble with one of the screws. Those warders are a recognisable bunch for anyone who was watching TV in the 1980s; they include Miriam Margolyes, Robbie Coltrane and Pam St. Clement – whose brassy Pat Butcher in EastEnders would also come to define the feminine spirit of the age.

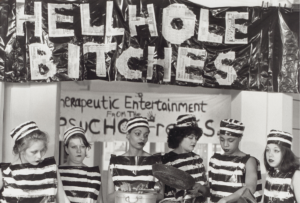

Most of the Borstal girls were played by less familiar faces. Amanda York played the lovestruck waif of the group, Carol, while Chrissie Cotterill was Annette, whose one aim is to release her baby daughter from a cold Catholic care home when she finally gets out of purgatory. It’s a film that’s both violent and compassionate, realist and oddly theatrical, not least when the ensemble gathers for an impromptu camp show, bedecked in black lipstick and bin bags as the “Hellhole Bitches” girl group. Music is important to the film: punk singer Honey Bane is among the cast, and it is soundtracked both by church organs and by dirty songs spun on the fly by Mandi Symonds’ Mac. Those tunes resound off the walls of the Surrey sanatorium in which the film was shot, after weeks of immersive rehearsals.

There’s a stark, almost monochrome palette to Scrubbers that renders it strangely timeless, but it’s anything but artificial, caked as it is in shit, blood and tears. The real stuff of life, as experienced by the working-class heroines of the 1980s – the survivors who demanded their right to fight back against the bastards, keep their dignity, and tell a really good dirty joke.

Scrubbers is available to watch on The Cinema of Ideas from 18 November – 2 December. From 7pm-8pm on Wednesday 24 November, Pamela Hutchinson will be in conversation with Scrubbers writer & costume designer Susannah Buxton to discuss the making of the film and its impact. Tickets are £5 and give you access to both the film and conversation. Book now.

Pamela Hutchinson is a freelance writer, critic and film historian who contributes regularly to Sight & Sound, the Guardian, Empire, Criterion, Indicator and the BBC. She has written essays for several edited collections and is the author of the BFI Film Classic on Pandora’s Box and the editor of 30-Second Cinema (Ivy Press). She tweets at @PamHutch.