Streaming on The Cinema of Ideas from 7-21 March, Restitution in Motion is an online season of films and discussions exploring historical and new approaches to restitution.

In this creative written response to the programme, Dr Lennon Mhishi (researcher at the University of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum) considers the forms and ways that restitution can occur.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

I am interested in the question of and demand for restitution as a process, not as an event. This means considering the various intersecting histories and factors accompanying the return of material subject to claims from different places in the world. It is restitution as building, as putting systematic mechanisms in place to address historical theft, violence, and erasure.

Amilcar Cabral, in the essay National Liberation and Culture:

History teaches us that, in certain circumstances, it is quite easy for a stranger to impose his rule on a people. But history equally teaches us that, whatever the material aspects of that rule, it cannot be sustained except by the permanent and organized repression of the cultural life of the people in question. It can only firmly entrench itself if it physically destroys a significant part of the dominated people.

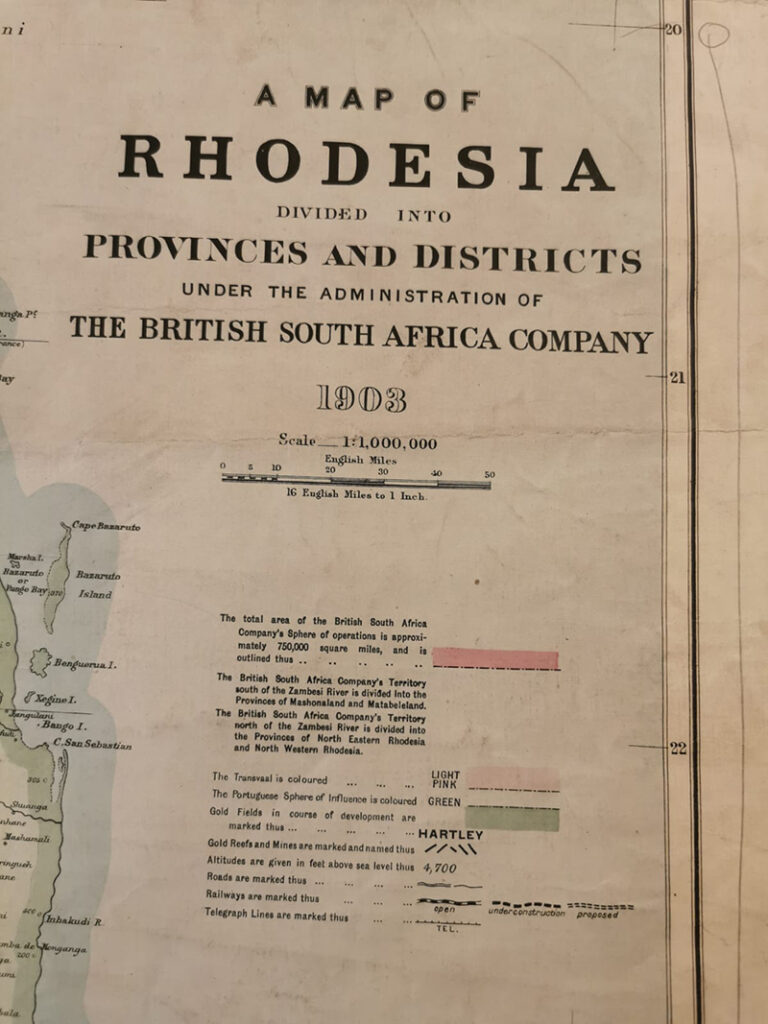

In Zimbabwe, the colonial institutional, legal and regulatory frameworks that governed African life across the spectrum were formed with oppressive and extractive intentions. These were accompanied by encampment, enclosure, containment and the allied punitive and extractive orientations. The early form of a museum in the country, then known as Rhodesia, focused on mining and ecology for extractive purposes. These corporate-militarist colonial adventures, legitimised by notions of ‘science’ and ‘knowledge’, are embodied in the museum, marking a specific conjuncture in the extractive histories that later sit in displays and catalogues and hold the violence and brutality in place in the museum.

This is an example of the shared histories of colonial incarceration, Black life, and the case for reparations and abolition transnationally, so what does this have to do with film, museums, archives and cultural institutions? The work of restitution here is also the work of imagining archival, museum and other institutional practices and processes that function away from the carceral logics of imprisoning people’s histories, cultures and knowledge and the disciplinary and punitive orientations that shape and accompany the presence of this material in the institutional space.

How can we relate material away from the carceral logics that often shapes how certain communities encounter the material and the architectures and infrastructures that contain them? By “contain” here, I am thinking not of how they constitute a collection or are stored, but precisely the functioning of these infrastructures as containment- places/spaces governed by carceral logics that limit the possibilities of what the material can become and that function in symbiosis with other similar infrastructures of containment. So situating an object in its location also becomes about how the material can escape various forms of imprisonment/confinement.

This capture and the process of limiting access and mobilisation into the present is what I am referring to as infrastructures of containment in my work. To contain[1]:

• to have something inside or include something as a part

• to keep something harmful within limits and not allow it to spread

• to control or hide a strong emotion, such as excitement or anger

• (of an object or area) to have an amount of something inside or within it

• to have as a part, or be equal to; include

• to keep within limits; not to allow to spread

The history of material that ‘sits’, in the way we reference a certain stasis in how the material is kept in place, simultaneously holding the sometimes violent and at times stultification- is also a history of connections that ensue to those places that the material has been, or passed through. The challenge is to think of the object not as an end in itself but as what it means to rethink what knowledge is held in this materiality. We become custodians of material in different ways, who accesses and uses it, and how various indigenous and counter-epistemologies and cosmologies can become part of how we understand this material.

Inviting different communities into the archives/storage/catalogue and the spaces where this material is contained is fraught. On what and whose terms access is provided, the possibilities thereof are not a process of absolution or a resolve.

Various African and African diaspora institutions and individuals are playing an indispensable part. Numerous museums, archives, film and other cultural and heritage institutions and their workers tirelessly (they do, of course, get very tired) enable access and are open to reimagining these spaces. This is not the work of a singular institution or individual, and the collaborative and transformative potential also lies in yielding away from investments in routine, custom and convention (this is how things have always been done) to opening our work to different possibilities (this is how the work can be done).

In a conversation I had in Berlin with Ambuya Stella Chiweshe, she argued that if the material comes from histories of colonial violence and deceit. It is heavy with the mourning and loss that accompanied its entry into the museum, and then it couldn’t be returned as it was. It needed to be ritually cleansed, and the spirits of those who toil in these subjects-objects appeased so that restitution can fully occur.

Are our current legal, institutional and infrastructural technologies alert to these hauntings, the voices recorded, the films made and kept, the anguish they hold, and the peace sought? Acknowledging that the material contained was part of technologies of everyday life means being responsive to the possibilities that restitution can take, as with indigenous rituals and ceremonies.

For material from historical moments of colonial violence, looting and cultural theft, containment and dislocation have been constitutive of how we encounter them. At this point, it’s no longer a question of whether restitution is desirable. It’s about the different forms that restitution can take, in addition to and beyond returning, object by object, with their own specific circumstances, material to various communities. In doing so, we acknowledge that we desire an engagement with this material not premised on relationships of domination and extraction.

The demand for a return is clear. The question of what to do with sound and film is equally significant as the question of the constitution of the materiality of the subjects-objects that are the focus of the conversations on restitution. Capturing the voices and images of different ancestors, moments of colonial violence, and the banality of coloniality should be inseparable from the broader concerns of restitution beyond the moment of return.

Sound and film as containers here, as also simultaneously contained, are part of the demand of the work of restitution. How do we read them, and what can we mobilise of them to escape these carceral logics? Can we remix them and mash them up to make new sounds and visions?

In response to some of the (sound) collections from the Pitt Rivers, I continue to work with artists like Charles Nyiha and Ibiye Camp, playing with mashing them and ideas of decay and the transformation of the sonic and the digital in shifting materialities. This is also an attempt not to reinscribe technologies of stasis and containment but to consider the possibilities for insurgent practice.

Listen: Nigerian Sacred Verses

Made in collaboration with Laura Kloeckner from Savvy Contemporary as part of the Berlin Biennale in September 2022 and titled Sonic Echoes, this experimental space was forged as an entry point into how to enact reanimation of this material from the archives. Artists Elsa M’Bala and Charles Nyiha, and the now late Ambuya Stella Chiweshe, performed in response to this desire to escape the static and carceral logics encountered in some spaces. Part of this attempt is also to recognise how embodied performance accompanies the reanimation and reactivation, recognising that this material is part of living cultures and of people who have a claim and stake to how, by whom, and where this material is used.

A community of filmmakers and practitioners is working and focusing on heritage and restitution. Ghanaian film maker Fofo Gavua has spoken to me candidly about film and cinema in Ghana and what they mean as a heritage to different Ghanaian communities. I have been fortunate to interact with Rebecca Ohene-Asah, from the National Film and Television Institute of Ghana, about how they are working on the archiving and restoration of some of the early Ghanaian soaps, such as Osofo Dazie, as cultural heritage. Similarly, the work of the June Givanni PanAfrican cinema archive, Jihan El-Tahri, Jean Marie-Teno, and Nii Kwate Owoo, amongst many others, recognises the importance of film in the space of culture and the work on restitution. Film carries both the tangible and intangible, and in the tools and technologies of capture, storage and preservation, as well as the representational elements that form the audiovisual experience, as material and affective.

I am considering carceral logics and institutional processes as out of time, in the same vein as one can think of Africa as being in the future. This is significant in two ways. In the first sense, subject-objects extracted through colonial violence and deceit are already placed outside their temporal and cosmological circulations. As such, the institutions that contain this material can be regarded as inhabiting spaces of temporal entanglement and cosmological rage, where many ancestors and material that seeks at least rest, and in other ways reactivation, are imprisoned.

The turning of African art and culture into caricature, myth and legend and superstition, and the concomitant objectification, are all sheltered in the ethnographic project. The gaze and exhibition of Africans, the presence of African ancestors as objects of display, the idea of ‘other’ cultures on display and the ‘universal’ on some raced-based, pseudo-scientific bases is out of time.

What these films reveal is what already has been and will be. Material that belongs to African communities and other dispossessed peoples is always theirs, even when they have been subjected to legal and regulatory frameworks that claim them as the inalienable property of museums and other institutions. In effect, the task of restitution is not of gifting but of giving back and giving up, of yielding to a historical fact that endures. Colonial ethnographic collecting does not emerge victorious in exchange for ‘modernity, science and knowledge’, and whatever other trappings of civilisational life are dragged along with coloniality as an extractive project.

There is no adversarial or gladiatorial contest for me in demanding what should be rightfully returned. The moral-ethical and legal conundrum exists along the continuum of the hegemonic attempts at holding in place a version of the world where justice is not possible.

Rather than a post-ethnographic framing, the struggle, in the way Belinda Kazeem Kaminski challenges us, is what it means to have an oppositional gaze. It also means seeing and looking at these histories differently, outside the colonial ethnographic lens. A sounding and visual practice not geared towards producing a type, tribe or hierarchy and unencumbered by the demands of taxonomy and imperial fashionings.

What does it mean to return something in a world supposedly without outlying areas? The outside is the zone of the zombie, yet those of us marked by flesh carry this outside, as always, potential expulsion. Where notions of sovereignty are shifting, dissolving, and subverted, and the boundaries (colonial, invented, structuring) are simultaneously hardened by the infrastructures of containment? Softened, like mudslides, by floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, and other impending forms of rage, from a planet exhausted by our will to extraction and abandonment, pollution that contaminates an epidemic society?

This gesture, which produces a cacophony of screams of agony, as if the very structure of legible life shifts with a return, is as heavy as gas. Does it slip through history’s flailing arms and hands, yearning to hold on, preserve, and lay claim to what might have been solid that now melts into the air?

Here we are confronted with what might be regarded as interminable and the structuring histories that produce this specific moment where new socio-economic and political configurations are taking shape. In my mother tongue, we say shiri ine muririro wayo haiuregi. A bird is not known to change its song. What sounds and visions are we attuned to, and do we hear and see something different on the horizon?

I have, for instance, returned to one particular object at the Pitt Rivers, described as a sword. This bakatwa, as it is called in what we understand as Shona, occupies an interesting space for me as evidence of some of the materialities of museumisation that emanate from the oppressive colonial regulatory frameworks. In a colonial setting where this object, described as a ritual sword, is also read as a weapon and disarming the local population is a necessary process of extraction and domination, the knife references, in addition to the weapons in the museum, the intersections of cosmology and imperial materialities. What is contained here are also the traces of lineage and ancestral worlds.

The qualities of a subject-object are thus understood not on the basis of what material exists in context but out of it, out of time. There is, of course, challenging work underway at the Pitt Rivers that is making these connections and recognising the multiple meanings and uses that material that has been museumised has to different communities worldwide.

The task or the demand for reanimation comes when there is a wider reckoning of what it has meant for countries to sustain histories of cultural destruction and what attempts to restitute might look like. Material that has become transformed over time, acquiring new qualities and energies — chemical and toxic, spiritual and symbolic — might not be reanimated but disposed of. Ancestors and other human parts kept in museums may need rest and dignity, decent burials and mourning.

A challenge arises when there is a perception that the films and narratives about restitution are at risk of reproducing the histories of domination and extraction that are being challenged. At epistemic and material levels, the questions of where the demand emanates from and who leads the conversation matter. This, at least as far as the work, refuses to reproduce the coloniality it seeks to escape. If we have historical film and sound archives, out of which more film and sound work is produced, which remain inaccessible to the communities made subjects of this conversation, then what is being restituted? What substantive shifts can we recognise that cease to make restitution merely symbolic but a transformative process that potentially revitalises cultural spaces as sites forging different futures?

I agree that restitution cannot be about return alone, although it is a crucial part without which we wouldn’t be where we are in the process. We must also be alert to the enduring coloniality of the attendant infrastructures that have been subsidised and are subsidised by ‘cultural’ institutions. Restitution is inseparable from the broader sociopolitical and economic entanglements within which the question of culture has always been entangled.

Where communities recognise the material as living, and in the case of film and sound, where this material can be mobilised in the present and future, contemporary art offers a way to engage the complexity of these histories and reimagine them into the future.

[1] https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/contain

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Dr Lennon Mhishi is a researcher with the University of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum, working at the intersections of colonial collections, restitution, contemporary art practice and epistemic plurality. His interdisciplinary work spans interests in the afterlives of slavery and colonialism, the African diaspora, mobility and displacement, music and belonging, and recently, creative heritage and community-based approaches to forms of exploitation forced labour and human rights in different African countries. He is particularly interested in film, music, sound and other arts-based, creative approaches to knowledge-making and engagement.

Restitution in Motion is streaming on The Cinema of Ideas until 21 March. Tickets for this programme are free, but we invite and encourage donations to Ciné-Archives to support their work on restorations of Med Hondo’s early work.