Streaming on the Cinema of Ideas until 16 December, Independent Miss Craigie is a fascinating new film about pioneering filmmaker Jill Craigie (1911-99), one of the first women to direct films in Britain and a passionate feminist who aspired to build a more equal society after WWII. Alongside the film, on 7 December we’ll be joined by a panel of guests including Lizzie Thynne (director, Independent Miss Craigie), Penny Woolcock (director, Tina Goes Shopping, One Mile Away, Ackley Bridge) and Ros Cranston (Curator of Non-Fiction Film and Television at the BFI National Archive) to discuss the work and legacy of this trailblazing filmmaker.

To accompany this event, Invisible Women’s Rachel Pronger writes about Craigie’s curtailed career, the challenges she faced to get her work made, and the reasons why her films still resonate today.

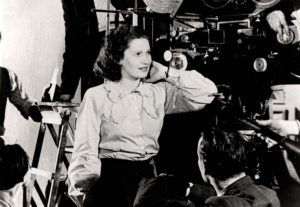

Jill Craigie was briefly a media sensation. In the 1940s, Craigie made a series of documentaries and was celebrated in the press as “Britain’s first female producer/director.” Glowing articles accompanied by staged images depicted the glamorous young filmmaker alongside patronising captions (“Craigie is proof that a career is no bar to domesticity!”). The decade culminated with the release of her first feature film. Blue Scar (1949) was an achievement by many measures – the only narrative feature to be solely directed by a British woman in the decade, the film was shot on location using innovative techniques and distributed outside of the studio system. Yet Blue Scar marked the peak of Craigie’s career. While she remained visible in public life – largely thanks to her marriage to politician Michael Foot– Craigie gave up filmmaking in the 1960s, having never made another feature.

At the heart of Lizzie Thynne’s Independent Miss Craigie, lies a question: why did Blue Scar mark the end, rather than the beginning, of Craigie’s filmmaking career? The answer tells us much about the conditions faced by female directors, while also opening up larger questions about a filmmaker’s role in society.

Jill Craigie was born in London in 1911, the daughter of a Russian socialite mother and Scottish father. Following an unhappy, financially unstable childhood, Craigie left school at 17 and became a journalist, writing horoscopes and agony aunt columns for women’s magazines. Her first marriage, to a producer who worked with Alfred Hitchcock, brought Craigie into the film industry’s orbit. As was the case for many women of her generation, World War II opened up new possibilities. After a period of writing scripts for the British Council, Craigie persuaded Rank Films to let her try directing.

Craigie’s directorial debut Out of Chaos (1942) is a striking slice of cultural history which attempts to understand the role art can play at a time of crisis. Several famous artists appear in stylish set-pieces – Paul Nash surrounded by wrecked planes, Henry Moore creeping around an air raid shelter, Stanley Spencer in a shipyard sketching on reams of toilet paper. Out of Chaos would be worth watching just for this footage of artists at work, but it also remains compelling because it beautifully captures the processes that translate trauma into art.

Aside from a glimpse of a painting by Evelyn Dunbar (the only woman to be employed as a full-time war artist), Out of Chaos’s subjects are all men. This is unusual for Craigie, a committed feminist who often centred women in her work. Craigie’s awakening had occurred during the war, when she stumbled across a copy of Sylvia Pankhurst’s The Suffragette Movement. By the 1940s, the fight for suffrage had been largely forgotten, and for Craigie, the book was a revelation. She became obsessed with making a film about this history, and even began working with Pankhurst on a script. Eventually, a lack of funding and development difficulties forced Craigie to abandon the project, and it would take until Sarah Gavron’s 2015 Suffragette before we would see a feature dedicated to the movement. The story of Craigie’s suffragette film is a tantalising “what if”. What if we hadn’t had to wait 70 years to see this story on screen? Could the precedent set by a 1940s film dedicated to radical women’s history have changed the course of the industry?

Like the onscreen art world in Out of Chaos, film at the time was suffocatingly male-dominated. The publicity surrounding the release of her debut perpetuated an inaccurate perception of Craigie as Britain’s first female director. Women had in fact been directing since the 1900s, and Craigie’s documentary peers included a number of women – Kay Mander, Ruby Grierson, Marion Grierson and Mary Field among others. However, while Craigie was not alone, her feelings of isolation were justified. After the war, many of the women who had stepped up to direct were pushed out of the industry. Craigie’s closest peer was Muriel Box, whose co-directed debut The Lost People was released the same year as Blue Scar. Box would go on to direct 12 features and is thought to be the most prolific British female filmmaker ever. Box though was very much an exception. For context, in the 1950s only two British women – Box and Wendy Toye – solo-directed feature films. It would take years for numbers to increase, and progress was not linear. In the 1970s, Jane Arden’s The Other Side of Underneath (1972) was the only narrative feature solely directed by a British woman to be released across the whole decade.

Craigie’s outsider status was reinforced by her socialism. Her passionate belief that film could transform society earned her powerful enemies. Rank’s Managing Director John Davis tore up the negatives for Out of Chaos and later attempted to shut down filming for The Way We Live (1946), a docu-drama about the post-war rebuilding of Plymouth. The latter sabotage was instigated by Conservative politician Nancy Astor, who disapproved of Craigie’s socialist message. That Astor (who was also an anti-Semitic Nazi sympathiser) was the first woman in Britain to serve as an MP, adds a bitter twist. Craigie and Astor were both outliers, but there was no sisterhood between these two exceptional women.

One of the strengths of Independent Miss Craigie is that it positions the viewer inside Craigie’s perspective. Thynne uses archive interviews and imagined first-person voiceover (performed by Hayley Atwell) to present Craigie as the narrator of her own story. With these devices, Thynne illustrates the filmmaker’s private struggles to reconcile her personal life – her role as a wife and mother – with her work and politics.

This deliberately subjective approach is appropriate. Craigie was an activist, and every aspect of her work was informed by her politics. The Way We Live, for instance, was Craigie’s attempt to democratise the town planning process and provide a mouthpiece for the concerns of the bombed-out working classes. Craigie developed the script with locals, casting non-actors to play versions of themselves, and ultimately persuading 3000 Plymouth residents to be actively involved in the production.

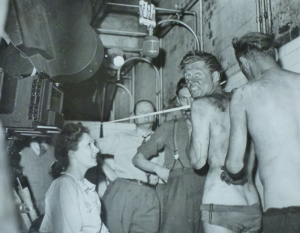

For her first feature, Craigie took this technique further. Blue Scar (1949) follows a mining community in the aftermath of the nationalisation of coal. Shooting on location in South Wales, Craigie was initially viewed with suspicion but ultimately won the locals over with her transparent, collaborative style. Craigie ran her scripts by the community, inviting criticism and editing in response to feedback. She also cast local people, sent her lead actor down the pit for a week to experience conditions first-hand, and enlisted disabled miners to advise on accuracy. On-set photographs show a pristine Craigie sat spotless in a sea of coal-smudged faces. The resulting film is a nuanced study of a neglected community which discusses pressing issues such as safety and workers’ rights without offering easy answers.

Made independently with no guarantee of distribution, Blue Scar was a gamble for all involved. In order to get the film seen, Craigie leveraged the press attention that had defined her career so far. Pragmatically aware that her photogenic looks made her a media-friendly proposition, Craigie turned the distribution saga into a publicity campaign, ultimately securing a limited cinema release. The film received positive reviews but only just broke even, leaving its director burnt out and disillusioned.

Blue Scar was not Craigie’s last gasp. She would go on to make several more documentaries, including To Be a Woman (1952), a campaign film addressing the gender pay gap. In an early example of crowdfunding, the project was paid for by members of the public and Craigie was so invested in the cause she offered to direct for free. Fittingly, To Be a Woman is her most explicitly feminist work, an invigorating call-to-arms that makes effective use of a strident female voiceover and a dynamic percussive score appropriately written by Elizabeth Lutyens, the first female British composer to score a feature film.

After Craigie stepped away from filmmaking in the 1960s, she remained a public figure, writing newspaper columns and sporadically appearing on talk shows as a “token feminist”. Her high-profile marriage forced Craigie to reckon with the tensions between her personal life and her politics. Foot was serially unfaithful and adamant that his career ambitions should come before his wife’s. Thynne includes a revealing clip in which the couple argue on camera about the disconnect between Foot’s public campaigning and his private behaviour. “I think you are a great feminist in theory” Craigie says damningly, “but in fact and practice, I don’t think you are.”

In the end, the marriage lasted, and it was Foot’s pension that would pay for Craigie’s last foray into filmmaking, after a three-decade hiatus. Two Hours from London (1995) is a harrowing television documentary which aims to draw attention to atrocities committed during the war in Yugoslavia.

Self-financed, produced and directed by the couple, and motivated by a sense of righteous injustice, the film provided a fitting coda to Craigie’s career. In 1999, Britain’s not-quite-first female filmmaker died at the age of 88.

Craigie’s refusal to compromise her politics stymied her career, but ultimately it is this sense of the personal that keeps her films alive. The context may have changed, but Craigie’s focus on perennial issues such as housing, class and the gender pay gap, still resonate. It is the very traits that hindered Craigie in the short term – her fiercely felt politics, her committed feminism, her subjective eye – that allow her work to live on. The films she left behind reflect the woman who made them: political, passionate and unapologetic.

Independent Miss Craigie is available to watch on the Cinema of Ideas until 16 December. From 6:30pm to 7:30pm on 7 December, we’ll be joined by a panel of guests for a live discussion of Jill Craigie’s work and enduring legacy.

Rachel Pronger is a freelance writer, curator and producer. She is also co-founder of archive activist film collective Invisible Women.