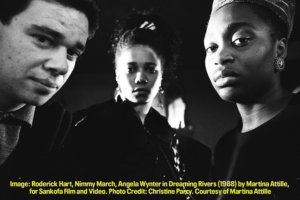

From 25-27 January, the Black Film Bulletin presents The Gaze on the Cinema of Ideas, a collection of short films by trailblazing British filmmakers from the African-Caribbean diaspora: Dreaming Rivers (dir. Martina Attille, 1988), Coffee Coloured Children (dir. Ngozi Onwurah, 1988) and Concrete Garden (dir. Alrick Riley, 1994). The Gaze is presented alongside a live Q&A with founding editor of the Black Film Bulletin Dr June Givanni and writer Jennifer G. Robinson at 6:30pm on Wednesday 26 January.

To accompany this event, Jennifer G. Robinson (Founder and Director of the Women Of The Lens Film Festival) writes about these three groundbreaking films and how each examines the experience of Black British life from the perspective of children.

Carefree, childlike wonder and freedom of expression have proven to be sparse attributes in characterisations of Black childhood on British screens. It is an ‘adultification’ of Black children that has real-time, real-life repercussions; a denial of an essential, humanising ideal of innocence, that robs Black children of their childhood, places adult responsibilities on their young bodies and puts them subsequently in danger.

The adult burden of ‘race’ for Black children is ever present in the films Dreaming Rivers (1988) by Martina Attille, Coffee Coloured Children (1988) directed by Ngozi Onwurah and Concrete Garden (1994) by Alrick Riley. Their experiences, voices and autonomy come to the fore in the three films. The documentation of first-generation Black and British children expressing their experiences with identity, how they feel about being themselves through ‘race’ is hard to find anywhere – on screen and beyond. We so often see ‘race’ happening to them, but we see limited examples of children being given the opportunity to tell us how they are feeling. So it is through these three films that we come to remember the importance of the British Black filmmaking of the time, and to understand their indelible mark on cinema with a contemplation on what future filmmaking could embody.

Martina Attille’s Dreaming Rivers is a maternal lament. It is a love letter for a mother who could not voice her own story; not only because of the burdensome pain of shielding children from emotional harm, but also; as with so many of her generation, she never thought that she could be allowed to express her emotions and should remain stoic and ‘strong’. Corrine Skinner-Carter’s Miss T is in a kind of purgatory, reminiscing of her life in England. For the children that gather around her, their story is of alternating identity, loss, feelings of abandonment and competition, – competition as demarcated by country of birth and age. Relationships in Dreaming Rivers mirror the rift of migration and the subsequent fraying of families who were born between their homelands and ‘ole-Blighty’.

Attille takes her time with her subjects and it’s a style of filmmaking that one has to search hard for in the myriad film titles that are released each year. The camera lingers over Miss T as she contemplates her life. The lens moves slowly over the accoutrements Miss T has gathered that signify the wealth of a Caribbean woman who had migrated to the UK. Dreaming Rivers gives us time. There is time to absorb not only the nuances of the children’s dialogue, detailing feelings they dared not utter whilst their mother lived, but also time to take in facial expressions of the children as they process their mother’s passing.

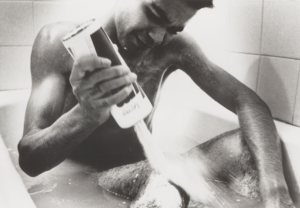

Self-realisation and self-acceptance are the youngsters’ ultimate comfort in Coffee Coloured Children. Ngozi Onwurah’s unflinching short provides stark sound and images of mixed-heritage children reliving their torture of being othered by ‘innocents’. It is not until a metaphoric exorcism of said torture and pain by fire occurs that the children can begin their evolution towards becoming unfettered human beings.

In Alrick Riley’s Concrete Garden, there is some semblance of sustained child-like quality that is distinct among this trio of films. It’s not long though before the spectre of ‘race’ rears itself. Concrete Garden depicts the way in which many first-generation children have had to make sense of the unrelenting racism they faced in British schools… on their own. Echoing similar themes of the previous films, Concrete Garden picks over the charged relationships between children of the same family, separated by age and country of birth.

In Concrete Garden, again, the element of time is gifted to the narrative. As Riley treats us to lingering shots of the protagonist Marcia, it is Marcia’s face that very much drives the film’s storytelling. Marcia’s voice-over as she reads her letters to her beloved grandmother in her distinctively Caribbean lilt is delightful. Despite Marcia having to fend for herself as she deals with very adult themes of racism, she still finds places of joy, play and excitement with her little brother in her ‘concrete garden’. This film is perhaps just one of two British films of the time that centres the voice of British Black ‘females’ – the other being Burning An Illusion (1981), directed by the late Menelik Shabazz.

Ahead of their time, Dreaming Rivers, Coffee Coloured Children and Concrete Garden lend themselves as batons for contemporary filmmakers’ attempts to capture childhood, the experience of migration and the process of navigating a sense of belonging, as seen through the eyes of children of the African diaspora. These films might also inspire a reappraisal of generic conventions of filmmaking; as whilst the successes of more commercial aspects of the artform cannot be ignored, the pioneers of Black filmmaking since the era of African-American auteur Oscar Micheaux’s prolific 1920’s ‘race movies’ have always charged ahead in voicing their own autonomous stories outside the conventions and limitations of the mainstream studio system. Today’s filmmakers have access to legacy films that offer opportunities to decolonize each aspect of the filmmaking process.

In a digital age defined by new technologies that offer evermore potential to engender cultural autonomy, and to connect artists and audiences throughout the diaspora, such filmmaking that speaks towards the decolonization of the moving image and the embodying of a Black ‘Gaze’, finds an essential home on platforms such as the Black Film Bulletin and within the June Givanni Pan African Cinema Archive. Dreaming Rivers, Coffee Coloured Children and Concrete Garden form an interdependent triumvirate of filmmaking that builds upon a bedrock of stylistic, historical, political and cultural memory, offering a vital legacy from which a new generation of filmmakers can draw.

Jennifer G. Robinson (@womenofthelens | womenofthelens.com)

The Gaze collection is streaming on the Cinema of Ideas from 25-27 January. At 6:30pm on Wednesday 26 January, Dr June Givanni (founder of the Black Film Bulletin) will be in conversation with Jennifer G. Robinson to discuss these trailblazing films. Book now.

With a career straddling film, education and PR, moving image curator and social media strategist Jennifer G. Robinson’s first foray into festival production came by way of the Black Filmmaker International Film Festival, founded by the late filmmaker Menelik Shabazz. Serving as Festival Coordinator inspired the desire to create her own festival – noting a distinct, yet subtle lack of support, collaboration and celebration of British Black women in the film industries that culminated in the launch of Women Of The Lens Film Festival in 2017.

Header image: Ngozi Onwurah. Image credit: Ngozi Onwurah and the British Film Institute